|

There is a cave inside, within, below, beneath.

Sometimes it seems that all that separates me from it is a thin sheet of paper, lit darkly, warmly from behind. When I close my eyes I can feel it, I can almost see it. I can almost become that emptiness.

0 Comments

New Mexico is full of wonderful characters, many of whom are disconnected from one another. Lots of people in Albuquerque and Santa Fe moved here from elsewhere, so we have distant networks around the world and smaller ones locally, networks that don’t always quickly or naturally overlap.

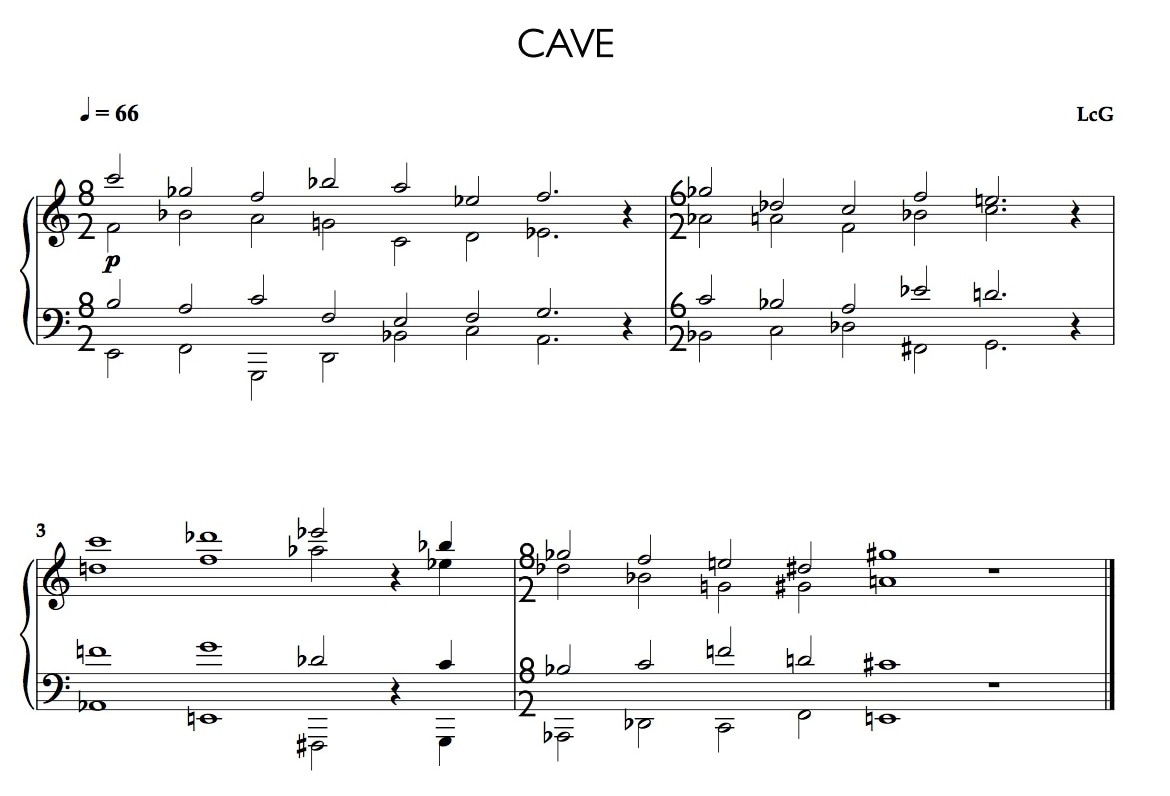

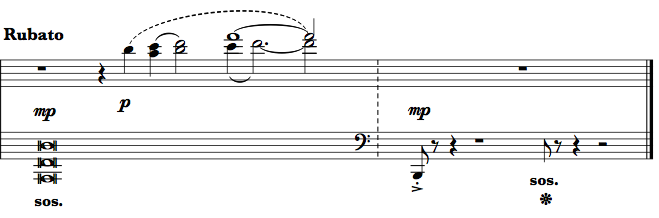

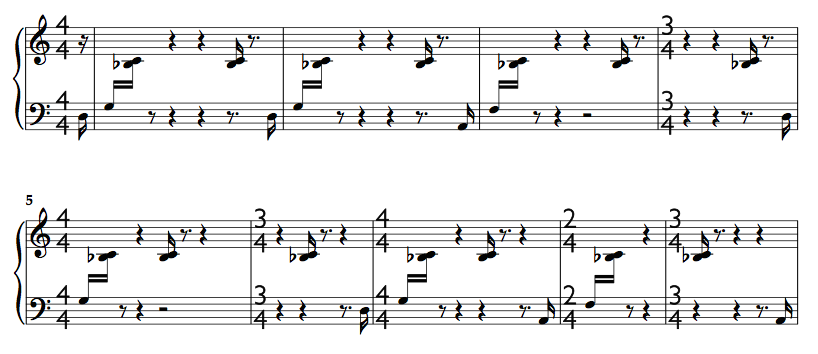

About a year ago I met one of these characters, Joseph Franklin, who founded the Relâche Ensemble in Philadelphia in 1977. He gave me a copy of one of Relâche’s CDs. I spun it in the car driving south on I-25 between Socorro and Truth or Consequences. The land opened up and the music started, and it was like a flashlight shone into a cave I didn’t know was there. The first piece was Robert Ashley’s Outcome Inevitable. There’s another version on YouTube. But in Relâche’s recording especially, with its tenser rhythms, the piece is like a lean, elegant mystery novel. The sentences are short, clipped. One wonders if the dialogue is less important than the things left unsaid. Each solo instrument gives its statement of events, and you have to try and figure out who the murderer is. I shared this impression with Joseph, and he told me Ashley was a big fan of film noir and detective stories. In this remembrance he tells a story of Ashley visiting Relâche’s office and commenting on its dark, wooden entry staircase, complete with a single hanging light bulb. Ashley’s most famous works, rightly, are the operas. I was floored by Dust; it’s a work of amazing cumulative power, with one of the great endings, an ending on the level of Before Sunset or Blood Meridian. The operas are overwhelming—by design, of course. They’re floods of information, and they have their own logic. The smaller pieces are useful as narrower wedges to get inside Ashley’s aesthetics. I’m thinking of For Andie Springer: Showing the Form of a Melody, “Standing in the Shadows,” by Robert Ashley (what a title!). Like Outcome Inevitable, it’s a piece of unbelievable simplicity, and simultaneously it is just the most mysterious and inexplicable thing you’ve ever heard. Like the songs at the end of Dust, like the melodies in Outcome Inevitable, the violin tones in For Andie Springer hang with almost naive earnestness, like a meditator who doesn’t realize he has levitated two inches off the ground. More than how Ashley wrote these tunes, you wonder how he ever thought to situate them so subtly, uncomfortably, perfectly. They don’t quite sit inside their forms. They wiggle. On the 21st I heard Roomful of Teeth in Santa Fe. They performed Ted Hearne’s monumental Coloring Book, which sets the words of three Black American writers of different generations: Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, Claudia Rankine. It was quite a piece to hear on a national day of marching, demonstration, and protest. I’ve written before, tongue somewhat in cheek, about my misgivings with the traditional practice of text setting. I have sometimes found it exploitative. But Ted gave me some new ways to think about it, in the music and in his onstage remarks. He acknowledged the “perversity” (his word) of a white composer setting these texts. He said he wanted to explore what it would feel like if he was the one saying these words, to see how it would shift their meanings. And he said that for him, setting these texts was a way of reading more closely. Now that, I like quite a bit. I like that humility, that respect. I like the way it puts the composer on the spot, doing the good and hard work of understanding. It doesn’t imply a complete understanding or vision of the text. It implies only sincere personal effort. Coloring Book is information-dense, somewhat like Ted’s big-time achievement The Source, which has not stopped revealing itself to me, even as it seems to hide more and more with each listen—behind its ambitious form, its distracting shifts, its sheer mass of content. (It’s something like Twitter, in that way. I’ve been off Twitter lately. I know I can’t blame it for the current desperations, but the fact that it’s T****p’s preferred medium, this fact does mean something.) So: text-setting as a way of reading more closely. Certainly Ted seems to have spent a lot of time with Zora Neale Hurston’s 1928 essay “How it feels to be colored me,” especially the section that comprises his fourth movement, “Letter to my father.” This is worth quoting in the composer’s formulation: “Him. He He has only heard what I I felt. He He is far away but I I see him. Him but dimly across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us. Us. He He is so pale with his whiteness then and I I am so colored. Music. The great blobs of purple and red emotion have not touched him. He is so pale with his whiteness then and I I am so colored.” The music pores over this text with such intensity that it becomes no longer a meditation but some kind of exorcism. Especially in the flow of the whole thirty-minute piece, it’s extremely moving. Ted really tried to understand what Hurston meant by “I am so colored,” and he tried seeing through the only spectacles he has, those of his own experience. Maybe that’s perverse, and maybe it’s futile. But he really tried, and in the process he wrung the emotion from this superficially simple text like it was a sponge soaked in wine. Roomful of Teeth opened the concert with the Allemande from Caroline Shaw’s Partita for Eight Voices. It was a joy beyond my expectations to hear this music live in person. The first thing Caroline says in the program note is that the piece is simple. Which is evidently some kind of defense mechanism, an intentional disarming of the listener, because it really isn’t true. I mean, it’s not Le marteau sans maître, but in its way the Allemande as dense as Coloring Book, dense with syllables and consonants, dense with energetic waves. What is simplicity, anyway? Something can be simple in one way and terribly complex in another. How about focus? What is focus? How about reading? I’m working on an album project called Inventions. It originated with my Piano Inventions from Banff in 2010, a set of solo piano pieces derived from recordings of free improvisations. I wrote another set in a similar manner in 2015. I recorded them the other day with John Dieterich, who is in a really good band and possesses some unusual microphones. As in much of my piano music, there’s some exploration of unique resonances set up using silently held keys and my favorite tool, the sostenuto pedal. This is the middle pedal of the piano, which—unlike the more commonly used damper pedal on the right—sustains just the notes you’re holding on the keyboard, rather than lifting the dampers for the whole instrument. A sound has four phases, they tell me: attack, sustain, decay, and release. Pianos, being percussion instruments, are most characterized by the first phase. You hit a note. That’s the attack. If you hold the key down (or if you employ the middle or damper pedal) you keep hearing sound, but you aren’t really hearing sustain; unlike, say, the human voice, we have no way on the piano of continuing or growing a tone. As soon as the note sounds, it immediately begins to decay. When you lift the key, or the pedal, there is a similarly audible release. The music of my Inventions operates under the premise that music takes place during the (non-notated) decay of tones, and at their (sometimes, in my system, emphasized) releases, not just at their (traditionally notated) attacks. But there is an equally characteristic second premise here: a flat refusal to explore the first one in any sort of systematic way. Because after all this isn’t really a discursive premise of an argument; what it is is a natural interest of a human being. Interests are like love. They aren’t so clearly delineated. Their subjects and objects are blurred around the edges. They don’t exist for a specific purpose. We don’t ask them to emerge and we don’t use them for anything. We just have them. And they shift as they will. So I might draw a comparison to a piece of music I’ve been thinking about lately: Dan Trueman and Adam Sliwinski’s album Nostalgic Synchronic, which explores and demonstrates Trueman’s software instrument the prepared digital piano. He hasn’t set up a complete compendium of all the instrument’s possibilities, but a left-brain effort has been made to show a range of its technical potentials. This connects with my old saw about “exploiting material” in composition. The question is whether one has subjected one’s ideas to a thorough going-over, or not. My argument has been, and remains, that while the first approach is perfectly valid (as the whole European heritage of classical music stands to demonstrate), the second is also. Example: the opening idea in one of my Inventions, “Church Dust.” I’m tempted to call it a groove, but it isn’t, because it never settles in. It does not predictably repeat, nor are the rhythmic variations logically explicated. They just flow from one to the next, at the speed of thought and with the logic of memory. This was an improvisation; so I took the first idea as a premise and continued and played with it, but I did not stop to notate it, analyze it, and consider my options. When it comes back slightly different later, it’s because I didn’t necessarily remember it the same way I played it the first time. John said something about writing through improvisation—that this way we arrive at different forms that we’d never create if we were working on paper. That’s a good point. Not just for macroforms but also for the individual variations in a single idea.

In this as in other things I have been guided by the flowing, not-quite-repeating music of Peter Garland. The ideas in his music feel connected, even when traditional motivic relationships are hard to isolate, because the ideas move from one to the next at the speed of thought. One of his longer pieces, like either of the two string quartets, proceeds like a long solitary walk. You might think of a memory, a person from your past, something about food, something about politics, something from a book you've been reading. On the surface, these objects of contemplation have little to do with one another. And yet meaning spontaneously arises from their juxtaposition. Connections, while not inherent, emerge. |

A Selection• Gone Walkabout

• Migration • Music as Drama • Crossroads II • 10 Best of 2014 • January: Wyoming and the Open • February: New Mexico and the Holes • Coming Up • Notes on The Accounts • Crossroad Blues • Labyrinths Archives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed