|

About two years ago I sat down to write an exegesis of one of my strangest, most personal, and I suspect least understood efforts, the short album Five Drawings by Joseph E Yoakum (2012). It's an old attic of a piece, creaky and dusty, full of trunks that haven't been opened lately. There is background noise; there is a great deal of what my friend Ben Hjertmann memorably called "fake silence" (a favorite concept in my recent music). In other words, I chose not to sweep the attic. I haven't dared write anything so messy since.

Here is the music, and a PDF of my Skeleton Key, which offers some further context and explanation, admittedly more autobiographical than musicological.

Additionally, just for kicks, there is this "bibliography" I composed around the time I was writing the first Yoakum drafts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY The Books -- Thought for Food (2002) Ornette Coleman Quartet -- Change of the Century (1960) Steve Coleman and Five Elements -- Harvesting Semblances and Affinities (2010) Chick Corea / Bela Fleck -- The Enchantment (2007) Miles Davis Quintet -- Miles Smiles (1967) Julius Eastman -- Gay Guerrilla (1979) John Fahey -- The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (1965) Peter Garland -- String Quartet no. 1: “In Praise of Poor Scholars” (1986) Brian Harnetty / Bonnie “Prince” Billy -- Silent City (2009) Charles Ives -- Piano Sonata no. 1 (1902-1910) -- Three Places in New England (1910-1914) The Microphones -- The Glow Pt. 2 (2001) Charles Mingus -- The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady (1963) Charlemagne Palestine -- Strumming Music (1974) Fausto Romitelli -- Professor Bad Trip (1998-2000) Giacinto Scelsi -- Konx-Om-Pax (1969) Salvatore Sciarrino -- Infinito Nero (1998) The Sea and Cake -- Nassau (1995) Kenny Werner -- Lawn Chair Society (2007)

0 Comments

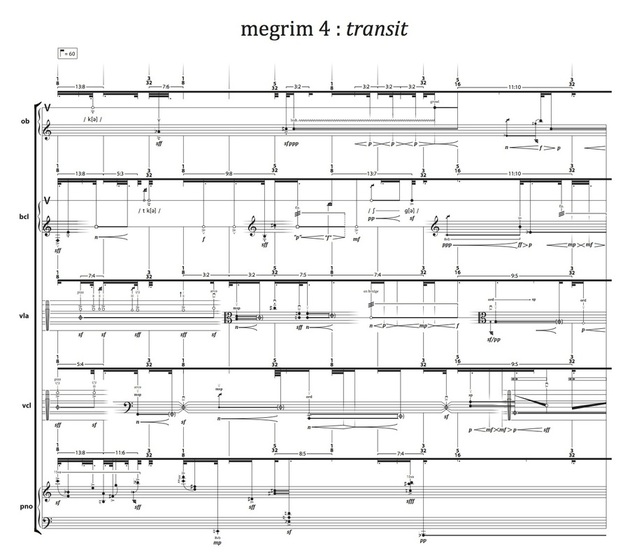

1. The story goes that Ike Zinnerman, who taught guitar to Robert Johnson, used to practice at night in a graveyard, sitting on a tombstone. I don’t know why I like that so much. I used to think about it when I sat down to practice piano—during the day, in a practice room, at a music school. It helped. 2. My friend Joan wrote an article about music by Andrew Greenwald and my friend Chris. “I am usually not very interested,” Joan writes, “in music that attempts to trigger effortless, straightforward communication.” A degree of obscurity—his word—gives him freedom as a listener, makes him a truer participant in the music: “I want to be able to actively create while listening.” Chris is, as Joan points out, an extremely good composer. I recorded a piano piece of his last year. The score is dense with nuance, though not rhythmically involved or timbrally specific to the extent of his more recent pieces, like megrims: 3.

In 2008 I met two friends at a conference. We were all grad-student composers, at three different schools. Friend A couldn’t believe Friend B had never heard of Helmut Lachenmann; Friend B couldn’t believe Friend A had never heard of Jennifer Higdon. 3a. Here is a short list of names I never heard mentioned by anyone in my Master’s composition program: Lachenmann, Scelsi, Sciarrino, Ferneyhough, Nono, Aperghis, Deleuze. 4. It has been written that degrees of complexity ebb and flow in musical fashion. In the middle ages one line became two, then four, until Renaissance counterpoint gave way to the textual directness of early opera, which built to the intricacies of Bach, which were followed by the galant style that built through the classical era to the nineteenth century’s deepening adventures in harmony that gave us the collapse of the tonal system in the early twentieth; and then what? Simplicity, yes, on the one hand; and deepening complexity on the other. Brian Ferneyhough visited Northwestern University for a conference last year; I went to one of the concerts. I gather that he rejects the term “new complexity,” as Steve Reich does the word “minimalism.” 4a. Today the culture’s attitude toward new artworks is generally one of exhaustion, and I’m not sure what that means for musical complexity. Today if you write an hour of music, the crucial thing is not the level of complexity featured therein, but where to find someone who has an hour. 4b. I’ve been reading Andrew Durkin’s Decomposition, which critiques the ways we talk about music and particularly the ways we construct our senses of its authorship and its authenticity. In fact he asks us to question whether we really know what music is. As the book aims for deconstruction, it is useful but occasionally bleak. If we agree to sacrifice conventional mental frameworks, how then should we think about music? I found myself searching for affirmative statements. I found one on page 165 of 303: “Ultimately, the only honestly ‘authentic’ option as fans, critics, or practitioners is agnosticism about our own experience and generosity toward our fellow listeners.” No definition of generosity is provided, but I think we all understand it, perhaps not as an independent concept but as a vector of effort. We can identify an example of its manifestation more easily than we can offer its definition. On page 301, complexity makes its appearance. “Creativity is chaos,” Durkin writes. “If you try to escape it, into the safety of clarity, you drown…I won’t end by advocating complexity for complexity’s sake, but rather complexity for honesty’s sake.” Honesty. The above comments apply. Durkin again, on the final page: “More important is whether we can learn—or perhaps relearn—to hear music, make music, and think about music in a way that shows we are truly comfortable with complexity.” The complexity to which he refers is not in the score of Lachenmann, but in the fact of Lachenmann’s coexistence with Higdon. Here is honesty. 5. These virtues are important because Durkin ends up arguing for a participatory musical ethic. He carefully describes the ways in which performers, composers, improvisers, audio engineers, technologies, and finally listeners all collaborate, all behave creatively. I’ve felt this way for years, which is why I use the phrase “music-making” so often. Like generosity and honesty, music is a noun best understood as a verb. As a concept it eludes us; as an activity, it sings. Eventually you have to accept that you're a good composer right now, the best you'll ever be, today; because otherwise, if you insist that through study or practice you can become a better composer tomorrow, then you'll want to start the piece tomorrow, and tomorrow by the same logic tomorrow again, and time escapes, and you never compose anything. Zeno's Paradox of Creativity: you have to start the piece today, or you never will. You actually have no choice. You are the best you'll ever be.

Perhaps the essential distinction is that between perfection and completeness. We'll never be perfect, but we are always complete. One fall night a few years ago I walked up to the red line platform at Morse and there standing, waiting for the southbound train, was a cute girl reading War and Peace. We boarded the same car. I sat down and got out my book—which was, of course, War and Peace. Between Morse and Belmont I don't think she looked up from her book long enough to realize that I was reading the same one. She must've been in one of the battle scenes. I was probably in the middle of one of the interminable domestic episodes. Anyway I didn't say anything, maybe because of the unwritten rules of big-city public transport, maybe because I was on my way to a first date and felt awkward. Turns out my date that evening was also a fan of Russian literature, though she didn’t like Tolstoy.

|

A Selection• Gone Walkabout

• Migration • Music as Drama • Crossroads II • 10 Best of 2014 • January: Wyoming and the Open • February: New Mexico and the Holes • Coming Up • Notes on The Accounts • Crossroad Blues • Labyrinths Archives

October 2020

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed