|

I am engaged in a late-game effort to learn George Crumb’s Eleven Echoes of Autumn for a concert October 12-13. There are the usual interior and exterior piano techniques, muting, harmonics, pencil erasers, whistling, chanting, et cetera. I showed someone one of the spirally pages. “Play anything!” she said. “Who will know?!”

This might feel true, to someone seeing or hearing Crumb for the first time, but it’s not. Crumb has his own dialect with its own rules. It’s incredibly logical, once you get into it. I’m not one of those people who can juggle pitch-sets in his ear while listening to Boulez or Carter; I’m not talking about mysticism or witchcraft here. Quite the opposite: the compositional means are pretty specific, maybe even too specific. Sometimes I feel like he wrote the piece immediately after walking out of the final exam for a set-theory class. So, I can’t just play anything. If I played “The Girl from Ipanema,” they would know. Okay, maybe that’s a bad example. If I started playing the national anthem, or “What a Fool Believes,” or the slow movement of the Hammerklavier, they would know. Especially after it went on for a while. I wrote a few undergraduate pieces that tried to rip off Crumb, Webern, Bartok in his night-music mode. This, as it turns out, is hard. It’s hard to write something that precisely spooky (Crumb), that wild-mercury (Webern), that serenely unsettling (Bartok). It’s hard to execute bombast like Beethoven or unpredictability like Cage. I once sat through a concert of piano works by Ferneyhough and a bunch of Ferneyhough-adjacent composers. All of the music thought it was intense and bewildering, but only the Ferneyhough piece actually hit that bar. Anytime you’re accusing a composer of being too overt, maybe what they’re actually doing is being clear with their intentions. The changing of the season is a gate. I often feel a vague sensation of expansion around the solstices and equinoxes—sometimes heady and enlivening, sometimes vertiginous and scary. Sometimes, a sort of time travel is possible.

On October 6 I am playing in public for the first time Ned Rorem’s second piano sonata, a piece I started learning as a freshman sixteen years ago this fall. The same day, my alma mater Illinois Wesleyan University presents a recital in honor of my late teacher, Larry Campbell, who for reasons now forever unknown told me to go listen to the Rorem Sonata one day. Rorem turns 96 next month. He still lives in New York. I went to the library and found the Julius Katchen recording and listened to the piece. It was the first, but not the last, moment in one of those library listening rooms when I felt I’d just been handed the key to the secret garden. For my senior composition recital I wrote a string quartet that quoted the Rorem Sonata. Taking after the Ives Concord, I wrote a clarinet solo in the last movement, and hid the player in the catwalks above the audience. Sometimes when I practice the Rorem I notice that someone hidden is listening, just out of view above the stage, on the edge of my periphery. Sometimes I catch those shadows as I play. When I look over in their direction they flee, of course. So I’ve learned to just keep playing. We’ve all heard undergraduates claim to have it. The truth is, we all have it.

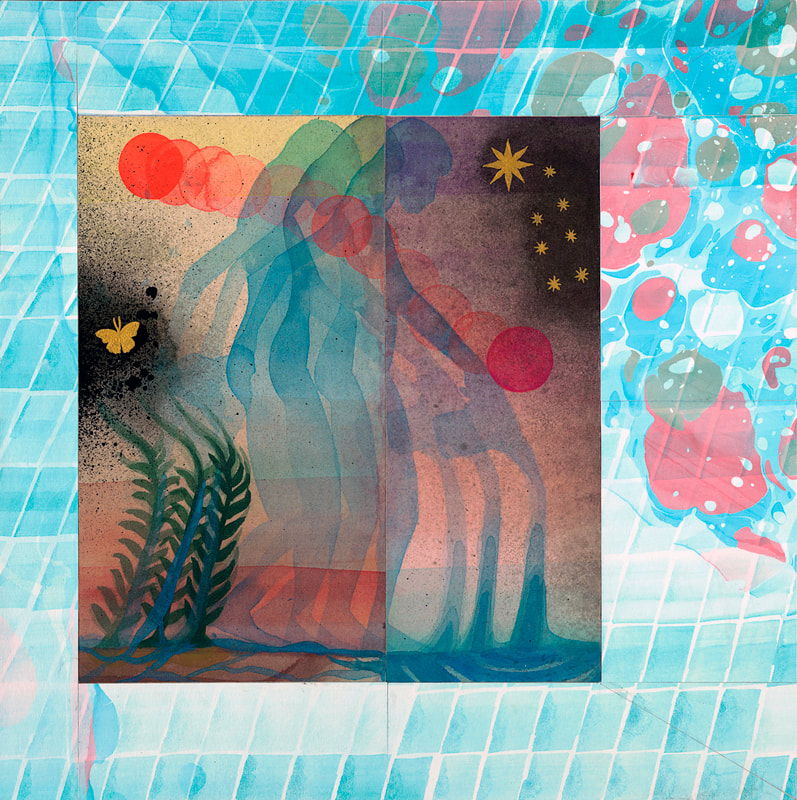

This weekend I’m playing a Handel Violin Sonata. A few winters ago I drove my 1996 Toyota Tacoma to the West Texas desert. We had a few cassettes: Steely Dan’s Aja, Hank Williams’ greatest hits, my own 25 to 40. After a few days deep in Big Bend Ranch State Park, we drove out on the dirt road one day and found Marfa Public Radio. It was the week before Christmas and they were playing “He Was Despised,” from Handel’s Messiah. Something happened between the music and the landscape in that moment, and I’ll never hear the song the same way again. I learned something about Handel that I couldn’t have learned in school. (Relevant new release: Rob Mazurek, Desert Encrypts Vol. 1) I spent my Labor Day weekend in the Jemez Mountains, roaming the San Pedro Parks Wilderness and reading Barbara Ehrenreich’s Natural Causes. It was a wild ride! She’s rhetorically unruly and charmingly cantankerous, and all told it’s a fast-paced 200-page polemic in which you’re pretty much guaranteed to high-five in agreement at some points while furrowing your brow at others. Among other things the book contains a feminist critique of medical culture, a Marxist critique of fitness culture, a general heaping of disdain toward Silicon Valley, a crash course in cell biology of the immune system, and a brief essay on the history of the notion of the “self.” She attacks mindfulness meditation and defends cigarette smoking. She’s good company and the bottom line is, you’re going to die, and so am I, and we’re not going to optimize our way out of this fact or work our way past it. All of that aside, I do have a lot of new work coming out over the next few months — work work work — a couple of them recently announced on the newsletter. The thirteenth Golconda, Ghost Stories, will release September 27, and the fourteenth, The Lost Forest, hits October 25. These two document the songs I wrote at PLAYA, in the high desert of central Oregon, last summer. Check out the beautiful cover art by Derek Chan: Keep an eye on Two Labyrinths Records, which is keeping it rolling for the rest of the year and into 2020 with these and other new things.

|

A Selection• Gone Walkabout

• Migration • Music as Drama • Crossroads II • 10 Best of 2014 • January: Wyoming and the Open • February: New Mexico and the Holes • Coming Up • Notes on The Accounts • Crossroad Blues • Labyrinths Archives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed