|

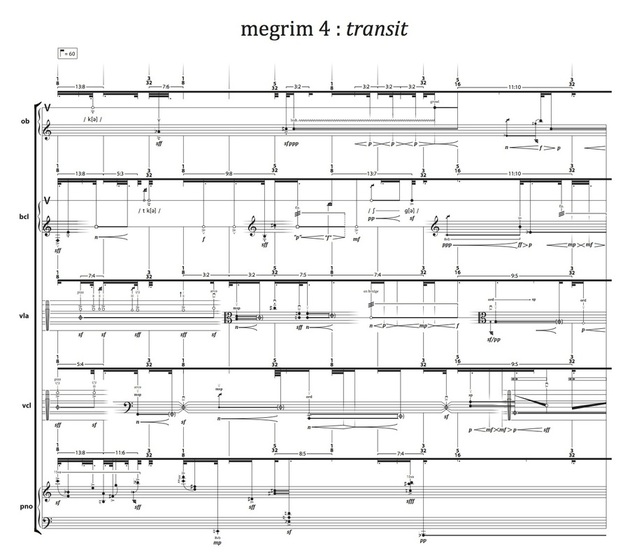

1. The story goes that Ike Zinnerman, who taught guitar to Robert Johnson, used to practice at night in a graveyard, sitting on a tombstone. I don’t know why I like that so much. I used to think about it when I sat down to practice piano—during the day, in a practice room, at a music school. It helped. 2. My friend Joan wrote an article about music by Andrew Greenwald and my friend Chris. “I am usually not very interested,” Joan writes, “in music that attempts to trigger effortless, straightforward communication.” A degree of obscurity—his word—gives him freedom as a listener, makes him a truer participant in the music: “I want to be able to actively create while listening.” Chris is, as Joan points out, an extremely good composer. I recorded a piano piece of his last year. The score is dense with nuance, though not rhythmically involved or timbrally specific to the extent of his more recent pieces, like megrims: 3.

In 2008 I met two friends at a conference. We were all grad-student composers, at three different schools. Friend A couldn’t believe Friend B had never heard of Helmut Lachenmann; Friend B couldn’t believe Friend A had never heard of Jennifer Higdon. 3a. Here is a short list of names I never heard mentioned by anyone in my Master’s composition program: Lachenmann, Scelsi, Sciarrino, Ferneyhough, Nono, Aperghis, Deleuze. 4. It has been written that degrees of complexity ebb and flow in musical fashion. In the middle ages one line became two, then four, until Renaissance counterpoint gave way to the textual directness of early opera, which built to the intricacies of Bach, which were followed by the galant style that built through the classical era to the nineteenth century’s deepening adventures in harmony that gave us the collapse of the tonal system in the early twentieth; and then what? Simplicity, yes, on the one hand; and deepening complexity on the other. Brian Ferneyhough visited Northwestern University for a conference last year; I went to one of the concerts. I gather that he rejects the term “new complexity,” as Steve Reich does the word “minimalism.” 4a. Today the culture’s attitude toward new artworks is generally one of exhaustion, and I’m not sure what that means for musical complexity. Today if you write an hour of music, the crucial thing is not the level of complexity featured therein, but where to find someone who has an hour. 4b. I’ve been reading Andrew Durkin’s Decomposition, which critiques the ways we talk about music and particularly the ways we construct our senses of its authorship and its authenticity. In fact he asks us to question whether we really know what music is. As the book aims for deconstruction, it is useful but occasionally bleak. If we agree to sacrifice conventional mental frameworks, how then should we think about music? I found myself searching for affirmative statements. I found one on page 165 of 303: “Ultimately, the only honestly ‘authentic’ option as fans, critics, or practitioners is agnosticism about our own experience and generosity toward our fellow listeners.” No definition of generosity is provided, but I think we all understand it, perhaps not as an independent concept but as a vector of effort. We can identify an example of its manifestation more easily than we can offer its definition. On page 301, complexity makes its appearance. “Creativity is chaos,” Durkin writes. “If you try to escape it, into the safety of clarity, you drown…I won’t end by advocating complexity for complexity’s sake, but rather complexity for honesty’s sake.” Honesty. The above comments apply. Durkin again, on the final page: “More important is whether we can learn—or perhaps relearn—to hear music, make music, and think about music in a way that shows we are truly comfortable with complexity.” The complexity to which he refers is not in the score of Lachenmann, but in the fact of Lachenmann’s coexistence with Higdon. Here is honesty. 5. These virtues are important because Durkin ends up arguing for a participatory musical ethic. He carefully describes the ways in which performers, composers, improvisers, audio engineers, technologies, and finally listeners all collaborate, all behave creatively. I’ve felt this way for years, which is why I use the phrase “music-making” so often. Like generosity and honesty, music is a noun best understood as a verb. As a concept it eludes us; as an activity, it sings. Comments are closed.

|

A Selection• Gone Walkabout

• Migration • Music as Drama • Crossroads II • 10 Best of 2014 • January: Wyoming and the Open • February: New Mexico and the Holes • Coming Up • Notes on The Accounts • Crossroad Blues • Labyrinths Archives

October 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed